This episode of the See America Podcast was written and hosted by Jason Epperson with narration by Abigail Trabue. Abigail Trabue’s part comes courtesy of “The Dog on the Catwalk.”

Listen below, or on any podcast app:

The See America Podcast is sponsored by Roadtrippers. America’s #1 trip planning app. Enjoy 20% off your first year of Roadtrippers PLUS with the code RVMILES917X.

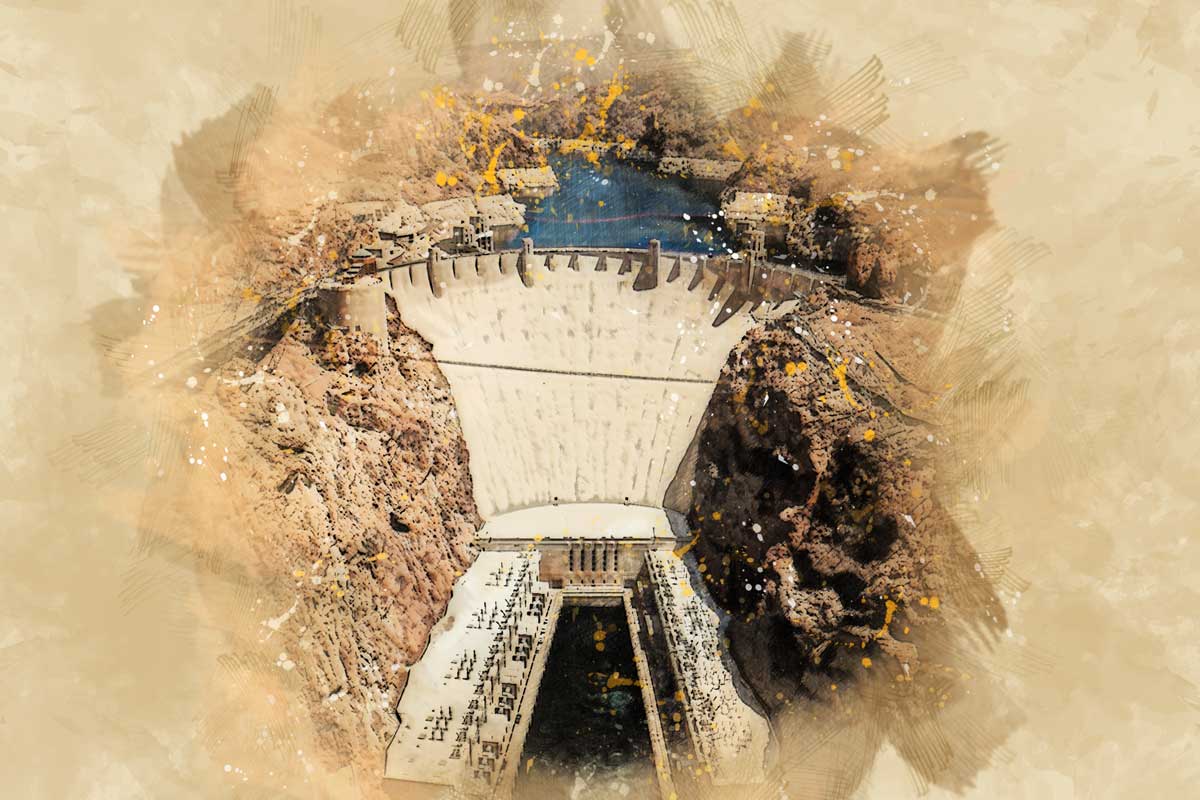

In the desert of the southwest sits a looming, concrete arch-gravity dam in the Black Canyon of the Colorado River, on the border between Nevada and Arizona. It was constructed between 1931 and 1936 during the Great Depression and was dedicated on September 30, 1935, by President Franklin D. Roosevelt. It was a massive effort involving thousands of workers, many who lost their lives. Originally known as Boulder Dam, today it provides power for public and private utilities in Nevada, Arizona, and California, and is a major tourist attraction; nearly a million people tour the Hoover Dam each year.

History of the Hoover Dam:

Since about 1900, the Black Canyon of the Colorado River and nearby Boulder Canyon had been investigated for their potential to support a dam that could control floods, provide irrigation water and produce hydroelectric power to the desert. In 1928, Congress authorized a project that would solve the need. The winning bid to build the dam was submitted by a consortium called Six Companies, Inc., which began construction in early 1931. Such a large concrete structure had never been built before, and some of the techniques were unproven. The torrid summer weather and lack of facilities near the site also presented difficulties. Nevertheless, Six Companies turned the dam over to the federal government on March 1, 1936, more than two years ahead of schedule.

The Hoover Dam wouldn’t be possible without a material that’s thousands of years old, having been used by the Romans and the Egyptians. Still, its secrets were mostly forgotten until the industrial age: Concrete.

Concrete consists of four ingredients-sand and crushed rock aggregate, water, and Portland cement. These must be mixed in the proper proportions to yield strong concrete. Aggregate is perhaps the most important of the materials in the concrete because it makes up as much as three-quarters of the Dam’s mass. The aggregate must be clean and free of clays, salts and organic matter. A source of aggregate near the Dam was needed so that it would not have to be transported too far.

Bureau of Reclamation prospecting parties searched the desert around Black Canyon for months, looking for a good supply of aggregate. Eventually, an alluvial lens just over six miles upstream on the Arizona side of the river was chosen as the source. Here, floodwaters had been depositing stones for millions of years. Some of the rounded stones were as much as 12″ in diameter and had been washed down from as far away as the Grand Canyon. The deposit covered more than 100 acres thirty to thirty-five feet deep.

A dragline was used to excavate the aggregate and load it into rail cars. The cars hauled the aggregate to a screening and washing plant on the Nevada side of the river at Hemenway Wash.

At the screening plant, four screening towers separated the aggregate into different sizes; fine, intermediate and coarse gravels, and cobbles 3-9″ in diameter. Anything over 9″ was run through a crusher and screened again. The separated gravel and cobbles were carried to the mixing plants by train.

The initial concrete required for the dam was mixed in a river-level mixing plant, which was located approximately 3/4 of a mile upriver from the dam site. This plant provided the concrete for the linings in the diversion tunnels and for the lower levels of the dam. It went into operation on March 3, 1932. The concrete was loaded into buckets that were transported to the site initially by truck. Eventually, the concrete buckets were transported by electric trains. For the first year of operation, nearly all of the concrete produced at this plant, almost 400,000 cu .yd., went into the linings of the diversion tunnels.

In the tunnels, the concrete buckets were moved by a gantry crane which ran on rails from one end of the tunnel to the other.

The first concrete was placed into the dam on June 6, 1933, using 4 and 8 cu .yd. bottom dump buckets. These buckets were lifted from the cars and lowered into place by overhead cable ways. There were a total of nine of these cable ways used to place the concrete. Five of the cable ways were connected to moveable towers, which allowed them to be repositioned to work on different parts of the dam when necessary.

As the dam rose in height, a new concrete mixing plant was constructed on the canyon rim. Completely automated, the hi-mix plant measured ingredients, mixed and dispensed the concrete. It was capable of producing 24 cu .yd. of concrete every three and a half minutes. The hi-mix plant was used to produce all of the concrete placed in the dam above the 992-foot level.

One of the problems was that in order to produce the strength of concrete the dam required, a very dry mix had to be used. There was very little time available to move the concrete from the mixing plant to the dam. If too much time was taken, the concrete would take its initial set still in the dump buckets and would have to be chipped out by hand. For this reason, the men who operated the cranes which moved the buckets into place were some of the highest-paid workmen on the project, earning $1.25 per hour. As each bucket was dumped, seven puddlers used shovels and rubber-booted feet to distribute the concrete throughout the form and pneumatic vibrators to ensure there were no voids.

As the dam began to rise to fill the canyon, it grew in fits and starts. Rather than being a single block of concrete, the dam was built as a series of individual columns. Trapezoidal in shape, the columns rose in five-foot lifts.

The reason that the dam was built in this fashion was to allow the tremendous heat produced by the curing concrete to dissipate. Bureau of Reclamation engineers calculated that if the dam were built in a single continuous pour, the concrete would have gotten so hot that it would have taken 125 years for the concrete to cool to ambient temperatures. The resulting stresses would have caused it to crack and crumble away.

It was not enough to place small quantities of concrete in individual columns. Each form also contained cooling coils of 1″ thin-walled steel pipe. When the concrete was first poured, river water was circulated through these pipes. Once the concrete had received a first initial cooling, chilled water from a refrigeration plant on the lower cofferdam was circulated through the coils to finish the cooling. As each block was cooled, the pipes of the cooling coils were cut off, and pressure grouted at 300 pounds per square inch by pneumatic grout guns.

To prevent the hairline fissures between the blocks from weakening the dam, the upstream and downstream faces of each block were formed with vertical interlocking grooves; the faces turned toward the canyon walls with horizontal, vertical grooves. When the concrete had cooled, grout was forced into these joints, bonding the entire structure into a monolithic whole.

Hoover Dam was the first man-made structure to exceed the masonry mass of the Great Pyramid of Giza. The dam contains enough concrete to pave a strip 16 feet wide and 8 inches thick from San Francisco to New York City. More than 5 million barrels of Portland cement and 4.5 million cubic yards of aggregate went into the dam. If all of the materials used in the dam were loaded onto a single train, as the engine entered the switch yards in Boulder City, the caboose would just be leaving Kansas City, MO. If the heat produced by the curing concrete could have been concentrated in a baking oven, it would have been sufficient to bake 500,000 loaves of bread per day for three years.

There are many stories surrounding the construction of the Hoover Dam. Too many to recount here, but there’s one that struck us in the heart.

The Dog and the Catwalk:

On the canyon wall, just across from the escalator leading to the Tour Center at the Hoover Dam, is a plaque dedicated to a dog. Puzzled visitors often ask the guides and guards why the plaque is there. The answers to these questions help keep alive the saga of the first and only Hoover Dam mascot.

Details of the mascot’s birth are a bit obscure, but he was likely born in the worker’s barracks. The dog’s rough black puppy fur did not smooth out entirely as he matured and he never quite grew up to his outsized paws, but perhaps these odd characteristics helped to endear him to the workers. He was hardly weaned when Mr. Hardy, a worker transport driver, picked him up one morning and tossed him aboard. When the dog first saw the dam, he knew that was where he belonged. It became his life. The only life he ever knew or wanted. Every morning he boarded a transport and put in a full day’s work along with the other workers.

He inspected everything daily. As the dam rose higher and higher he had to ride the skips, a type of open-air elevator, to cover the ground. When he wanted to board a skip, he barked, and the operators always stopped for him. The mascot would hop aboard and bark again at the level where he wished to get off.

Trainers will tell you that one of the most difficult tricks to teach an animal is to get them to walk on any swaying, unstable surface, but Hoover Dam’s mascot raced happily back and forth across the swinging catwalks slung across the canyon seven hundred feet above the Colorado River.

The Hoover Dam mascot was not a one-man dog. He had no master. He belonged to the dam and everyone connected with it, and they all belonged to him! If he decided to work overtime at his favorite job of chasing ring-tailed cats that infested the tunnels, he hitched a ride back to town in the first car, truck or transport that happened along. No one ever remembers him accepting a ride from anyone not connected with the dam. How he could differentiate between dam workers and casual visitors no one could figure out, but it is a known fact that he did.

Everyone wanted to feed the dog, and being a dog, he found it hard to refuse. He became quite sick. The worried workers then decided that he needed supervised feeding, and arrangements were made with the commissary to feed him as word was passed to all workers not to offer him any snacks.

The commissary packed a lunch for him every day and he soon learned to carry it in his mouth when he boarded the transport. At the construction site, he placed the sack alongside the workers’ lunch pails and went about his business. When the whistle blew, the dog raced for his sack and sat patiently until someone opened it for him.

Workers leaving the job frequently stopped at the commissary and left a few dollars with the manager – “Just to see that the dog gets fed well.” These contributions soon grew to a respectable sum and a bank account was opened for the Hoover Dam mascot.

The money paid for his food, dog license, and some sleeping baskets (which he never used) and silver collars that he detested. Sometimes these collars were stolen by souvenir hunting tourists.

The fund also paid for advertisements in the Boulder City and Las Vegas papers, such as this one.

I Love Candy But It Makes Me Sick.

It Is Also Bad For My Coat.

Please Don’t Feed Me Any More.

Your Friend, The Hoover Dam Mascot

One evening, Chief Ranger Peterson was notified that a group of workers was beating a man. Chief Peterson dashed to the scene and broke it up. When he learned the cause of the riot, the Chief told the victim he would like to see the job finished but it was his duty to stop it. The Chief escorted the bloody and bruised man to the town limits and told him never to come back. The man had made the near-fatal mistake of kicking the Hoover Dam mascot.

After the dam was completed, the dog took it upon himself to see that the rule “NO DOGS ALLOWED LOOSE ON DAM” was rigidly enforced. His ironclad insistence on the letter of the law caused some embarrassment to members of the Guide Force, but these skilled diplomats always managed to convince indignant pooch owners that the mascot actually owned the dam. The Bureau of Reclamation merely built and operated it for him.

On a day when the blazing desert sun, combined with a blast furnace wind, pushed the thermometer over the 120-degree mark, the dog found a spot of shade under a truck. The driver never noticed the sleeping dog when he started up and drove off.

News of the fatal accident was phoned to town and it was the quietest afternoon Boulder City ever experienced. Later, rough, tough, hard-rock men wept openly and unashamed as they slammed their ear-shattering jackhammers into the hard rock cliff, carving out the grave which was to be the Hoover Dam mascot’s tomb.

So, in death as in life, the Hoover Dam mascot looks upon the dam he loved for as long as it will stand.

Know Before You Go:

When Hoover Dam was built in the 1930s, the great dam was known for its engineering superlatives. It was the highest dam ever built, the costliest water project, home of the largest power plant of its time.

Today, it’s clear that the dam is not only an engineering wonder. It’s a work of art. Few structures in America display the diversity of design and craftsmanship that you see at Hoover Dam. It is a showcase of seldom-seen skills of artists and artisans–beautifully presented terrazzo tiles, sculpture, metalwork, and even military emplacements.

The streamlined look of the completed project was influenced by two men who were not engineers: architect Gordon B. Kaufmann, known for his design of the Los Angeles Times Building, and artist Allen True, whose murals are prominent in the Colorado State Capitol in Denver.

Kaufmann was retained to counterbalance the engineers’ focus on “functionality rather than aesthetics.” He simplified the dam’s original design and replaced Americana ornamentation like eagle heads with the flowing lines of Modernism and Art Deco. He transformed the power plant with color and facades. He blended four protruding towers on the crest into the face of the structure. He smoothed the upper portions of the four intake towers and reworked the two spillways to accent Art Deco elements.

“There was never any desire or attempt to create an architectural effect or style,” he later explained, “but rather to take each problem and integrate it to the whole in order to secure a system of plain surfaces relieved by shadows here and there.”

Allen True assisted Kaufmann with interior designs and color. True was responsible for one of the dam’s most distinctive motifs–the Southwestern Indian designs in the terrazzo floors. True linked Native American geometric concepts with Art Deco design. Many of the Indian designs were based on centrifugal themes, which related to the turbines in the power plant. He used black, white, green, and dull-red ochre chips in the terrazzo floors to contrast with the black marble walls. He specified the red color for the generator shells in the power plant, a sight that still commands visitors’ attention.

You can see the power plant and terrazzo work during a tour of the dam. Following an elevator descent of 530 feet, you emerge into seemingly endless galleries. There you find gleaming terrazzo floors imbedded with the Southwestern Indian patterns adapted by True from baskets, pottery, and sand paintings.

On top of the dam, two “Winged Figures of the Republic” dominate the Nevada approach, They are the work of sculptor Oskar J.W. Hansen, a Norwegian immigrant who was appointed a consulting sculptor by the Secretary of the Interior following a national competition. Hansen said the 30-foot bronzed statues represented “that eternal vigilance which is the price of liberty.” Hansen’s figures flank a 142-foot flagpole. In front of this array, he placed a terrazzo star map depicting the celestial alignment from that site on the evening of September 30, 1935, the day President Franklin D. Roosevelt dedicated what was then called Boulder Dam.

Hansen also created the nearby bronze plaque memorializing the 96 workers who died during construction of the dam. An inscription proclaims, “They died to make the desert bloom.”

The other curiosity stands above the dam. If you look at the Arizona (eastern) side of Lake Mead, you will see a cubical silhouette. This is a gun emplacement built during World War II. As a major source of electrical power for the defense industry, Hoover Dam was considered a primary military target. Of several bunkers that guarded the dam in wartime, this one is the last survivor.

The pillbox, constructed of steel and concrete and veneered with local rock, is 24 feet long and has six gun ports. It was built by a military police battalion soon after the attack on Pearl Harbor, according to Lincoln Clark of Las Vegas. A retired U.S. Army lieutenant colonel, Clark was a first lieutenant when stationed at the dam in 1942. He and his fellow soldiers guarded the dam and escorted civilian vehicles across it. One soldier was always inside in the bunker, Clark recalls, and a squad of riflemen was scattered in the rocks 24 hours a day.

The heavily traveled U.S. Route 93 (US 93) ran along the dam’s crest until October 2010, when the Hoover Dam Bypass opened. The roadway on the Arizona side of the site has been closed. Vehicles can still cross the dam to visit the Arizona viewpoints and concessions, but all

are required to turn around and re-enter Nevada to access Highway 93.

All vehicles entering the dam site are subject to

inspection by officers at the security checkpoint located in Nevada, approximately one mile from the dam.

Passenger vehicles with a cargo capacity of one-ton or less can cross, including automobiles and light trucks, and RVs.

There’s a fee to enter the Visitor Center and observation deck, and an additional fee to tour the Power Plant

Connect With Us

Join the See America Facebook Group here. You can also follow See America on Facebook, Instagram, and Twitter.

Find more resources for the U.S. based traveler and National Park enthusiast at RVMiles.com.

If you’re a National Park lover, check out the America’s National Parks Podcast, or come listen to Abigail and me talk about our life on the road with our three boys on the RV Miles Podcast. Paragraph

Don’t forget to take advantage of the Roadtrippers PLUS discount:

The See America Podcast is sponsored by Roadtrippers. America’s #1 trip planning app. Enjoy 20% off your first year of Roadtrippers PLUS with the code RVMILES917X.